|

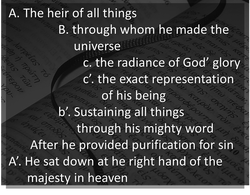

Last week we began this two part series on the descent and resurrection of Jesus the Messiah. However, it ought to be a three part series, in fact, for the descent, resurrection, and ascension are all part of the same theme: The exaltation of the Person of Christ. While the Cross is the victory over the powers of Satan and the power of sin, the resurrection and ascension are God’s vindication of his Son. But then why include his descent into that category? Surely his descent into Hades is more closely linked to his death upon the cross, as we saw last week, for it fulfils the same themes as the atonement. Yes, this is true. But we must remember that the entire Easter narrative is part of the same theme: the conquering of sin, death, and the devil. Last week we saw Jesus proclaiming his victory over sin by suffering the torments of hell upon the cross in judgment on our behalf, and over Satan by descending into hell and not being held by death. This week we will see how by his resurrection he proclaims his victory over death itself, the great enemy brought about by sin, and through this how he ushers in the new creation. Jesus’ victory over the power of death Although Martin Luther believed that the article upon which the church stands or falls is justification by faith, according to Paul it really is the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. J.I. Packer writes, “Had Jesus not risen, but stayed dead, the bottom would drop out of Christianity…”[1] But what sort of resurrection are we talking about? Was it physical or spiritual? What did the early Christians believe? In a massive 750+ page scholarly defence of the physical resurrection of Jesus from the dead, N.T. Wright opens by stating, “it has become accepted within much New Testament scholarship that the earliest Christians did not think of Jesus as having been bodily raised from the dead; Paul is regularly cited as the chief witness for what people routinely call a more ‘spiritual’ point of view. This is so misleading (scholars do not like to say that their colleagues are plain wrong, but ‘misleading’ is of course our code for the same thing) and yet so widely spread that it has taken quite a lot of digging to uproot the weed, and quite a lot of careful sowing to plant the seed of what, I hope, is the historically grounded alternative.”[2] I can only refer to the work itself for anyone interested in the subject, but here I will put forward a defence in light of what the Creed affirms, and then what Jesus’ resurrection means for us. Jesus was raised bodily When the Creed affirms, “On the third day he rose again,” it is not referring to some spiritual resurrection from the dead, for at the moment of death Jesus would have been in a spiritual resurrection! Rather, what the Creed most emphatically affirms, along with the apostolic teaching on the subject, is that Jesus rose physically from the dead. This was, after all, the testimonies of the early disciples, which was reflected in the writing of the gospels. Jesus appeared in bodily form to many people who knew him well (1 Corinthians 15:1-11); in his resurrected state he ate food (Luke 24:41-43), he had people touch him and feel his body (John 20:27-29; 1 John 1:1-3); Jesus taught and gave instructions (Luke 24:13-35; Matthew 28:16-20; Acts 1:6-8). On the basis of these appearance, Wright argues against three incorrect explanations for this phenomena: Resuscitation, not resurrection. One of the objections given to the historical resurrection account of Jesus, is the seeming ignorance of the ancient people to be able to medically determine whether or not someone was officially dead. For this reason, they argue, Jesus was probably not dead, and was resuscitated later. However, Wright points out that “Even if the Roman soldiers, seasoned professionals when it came to killing, had unaccountably allowed Jesus to be taken down from the cross alive, and even if, after a night of torture and flogging and a day of crucifixion, he had managed to survive and emerge from the tomb, there is now way he could have convinced anyone that he had come through death and out the other side. He would have had to be helped through, at best, a long, slow recuperation.” In this sense it would have been impossible for Jesus to be vibrantly present three days later, teaching, eating, and walking about. Cognitive dissonance. Some have speculated that the traumatic experience that the disciples went through after their hopes in Jesus' mission had been dashed by his death, lead to what professional sociologists call “cognitive dissonance.” In other words, they argue that the disciples so believed in Jesus and his mission that they lived in denial and continued to talk about him as if he were still alive. Wright points out that “Nobody was expecting anyone, least of all a Messiah, to rise from the dead. A crucified Messiah was a failed Messiah.” This comes through strongly in the gospel where, rather than speaking about Jesus as if he were still alive, the disciples had locked themselves away for fear that the same fate may befall them (John 20:19). These disciples were not living in denial. They literally thought that this was all over, as reflected by one of the statements by some disciples who said, “we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel” (Luke 24:21). Ancient superstitious beliefs Another argument that Wright proves is unconvincing is the widely held idea that ancient people were naturally superstitious, and that there were many accounts of various dying and rising gods in the ancient world that Jesus' followers merely adopted as their own. However Wright argues, “But – even supposing Jesus’s very Jewish followers knew any traditions like those pagan ones – nobody in those religions ever supposed it actually happened to individual humans.” Jewish monotheism was so strict, that even Paul initially opposed the church’s teaching about Jesus with the belief that this was leading other Jewish people into idolatry (see Acts 22:3-5). It was not common for Judaism to hold such beliefs, and even Paul had to have a blinding experience encounter with Jesus before he believed this was true (Acts 9).[3] Ok, so perhaps, if there was a resurrection, it wouldn’t have been falsified for the above reasons. But how can we know that, historically speaking, there ever was a resurrection? Gary Habermas gives ten historical facts which “are agreed to by virtually all scholars (even of differing schools of thought) as historical facts, of which we will only mention 6:

While these historical evidences may not convince all people as to the veracity of the New Testament claims, they nonetheless are agreed upon by scholars that an explanation must be given as to why this happened. It does not do justice to merely dismiss ancient folk as superstitious, for as Wright has convincingly argued in The Resurrection of the Son of God, ancient people were not as superstitious as we might think. People didn’t think that dead people rising are normal occurrences. Rather, we even have the episode in the gospel narratives of Thomas, who would not believe that Jesus had risen unless he could verify it himself (John 20:24-29). The only logical explanation that we have is that the early disciples really did believe that Jesus actually rose from the dead, and had appeared to them in physical form for numerous days after his resurrection, and as we have seen above, this wasn’t because they were living in denial! But the question we have to ask next is, what does Jesus’ resurrection mean? The meaning of Jesus’ resurrection But the resurrection is not just something that happened in history alone. It is an event that is laden with meaning. Michael Bird brings out four significant things that we can know as a result of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead.

Conclusion When the Creed affirms Jesus' bodily resurrection from the dead, it is affirming no less than his physical resurrection, but also much more. Because Jesus has been raised from the dead, we can know with certainty that the victory has been won on our behalf. This is what we discussed in the past two weeks. However, it also gives us courage in the present to know that we now can live a new life in Christ, and that we live for a kingdom that will endure. We therefore are to pattern our lives according to this kingdom, and not fall trap to the lie that the present world is all there is. As Christians, we live out the resurrection by our conduct, allowing the resurrection of Jesus to determine our ethics, our moral standard, and, though we build in this present world, we ultimately are to build the kingdom of Christ! [1] Packer, J.I. 1994. Growing in Christ. Wheaton: Crossway Books, pg. 59. [2] Wright, N.T. 2003. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pg. xvii. [3] See Wright, N.T. 2006. Simply Christian: Why Christianity Makes Sense. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, pg. 111-114. [4] Habermas, G. 1980. The Resurrection of Jesus: An Apologetic. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, pg. 33-38. [5] Bird, M.F. 2016. What Christians Ought to Believe. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 155-158. Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance.

0 Comments

Last week we looked at the necessity of the suffering of Jesus as the Messiah, and that this meant both victory over the powers of darkness and redemption from the power of sin for God’s people. This is the meaning of the death of Jesus upon the cross. But what happened after the cross? I mean, the whole reason we have Christianity and Easter is not because Jesus died an atoning sacrifice for sinners alone, but because something remarkable happened after the death of Jesus on the cross. The Apostle’s Creed next affirms that Jesus “descended into hell,[1] and on the third day he rose again.” But what in the world does it mean that Jesus “descended into hell”? And how did he rise from the dead? This week[2] we will deal with the first of these two controversial statements, “he descended into hell”, and next week we will see how the Christian faith hinges upon the resurrection. In other words, without the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, there is no Christianity (1 Corinthians 15:14). But, first, we must deal with this cryptic statement found in the creed, “he descended into hell.” Jesus’ victory over the power of hell There are two interpretations on this article which are prominent, and they emphasise either Christ’s victory over sin, or his victory over Satan and his emissaries, both of which are inferred from Jesus’ suffering upon the cross. We looked at this last week in more detail. We will deal with the former first, and then the latter. Interpretation 1: Christ’s Victory over Sin The Heidelberg Catechism (henceforth HC) asks the question, “Why is there added, ‘he descended into hell’?”[3] The reason why it states “Why is there added,” is because this article in the Apostle’s Creed was only added much later, perhaps in the fourth century,[4] and so is not confessed by all churches who hold to the Apostle’s Creed.[5] Therefore we understand that this article’s pedigree is to be held with suspicion. Nevertheless, the HC proposes an answer, “That in my greatest temptations, I may be assured, and wholly comfort myself in this, that my Lord Jesus Christ, by his inexpressible anguish, pains, terrors, and hellish agonies, in which he was plunged during all his sufferings, but especially on the cross, has delivered me from the anguish and torments of hell.” In other words, the HC follows Calvin’s interpretation, which states, “If Christ had died only a bodily death, it would have been ineffectual. No – it was expedient at the same time for him to undergo the severity of God’s vengeance, to appease his wrath and to satisfy his just judgment. For this reason, he must also grapple hand to hand with the armies of hell and the dread of everlasting death.” It would seem that Calvin, though not entirely in full agreement with Aquinus, for he still maintains that the entire event happens on the cross, but still follows Thomas Aquinus on this point to some extent who writes, “I answer that It was fitting for Christ to descend into hell. First of all, because He came to bear our penalty in order to free us from penalty, according to Is. 53:4: ‘Surely He hath borne our infirmities and carried our sorrows.’ But through sin man had incurred not only the death of the body, but also descent into hell. Consequently since it was fitting for Christ to die in order to deliver us from death, so it was fitting for Him to descend into hell in order to deliver us also from going down into hell.”[6] So while the HC and Calvin keeps the torment that Jesus suffered as metaphorical of the experience of hell on our behalf, Aquinus seems to go further and suggest, along with the plain reading of the Creed, that Jesus actually descended into hell. Yet, the entire reason for this still remains to suffer the torments of hell on behalf of those who deserve hell itself. In this sense, Jesus conquered sin fully and made full satisfaction for our sins. Interpretation 2: Christ’s Victory Proclamation Michael Bird has shown in his exposition that there is confusion because of “the failure to distinguish between Hades and hell in various versions of the Creed.”[7] Since the 17th Century, hell in the English had come to be a place of judgment and torment to which Satan and his enemies were assigned, but prior to the 17th Century referred to the place of the dead, or, Hades.[8] Bird also shows how this confusion crept into the Latin versions of the Creed with the use of inferus which refers to the place of the dead, or Hades, and infernus which meant the place of torment and judgment.[9] He shows how in some of the earlier versions of the Creed in Latin had descendit ad inferus, but in the fourth century it was changed to infernus. Bird therefore argues that a better translation of the creed, and a more biblical understanding, would be to render this article as “descended to the place of the dead.”[10] Bird shows how the Greek word for Hades is used in the New Testament for the place of the dead, translating the Old Testament concept of Sheol, and that in the New Testament Gehenna came to refer more properly to hell as a place of torment and judgment for the wicked. But for Bird, hell is a place of eschatological judgment that happens at the end of time after the judgment seat of Christ, and so is not a place which has yet been created.[11] In other words, Bird sees the reference to Hades as a place of the dead, like Sheol, which is “the waiting place of the dead… as they wait for the final judgment, while hell is the place of everlasting punishment and eternal separation from God.”[12] Hades, in this sense, is still a place of consciousness, and has a place for the wicked waiting judgment and the righteous experiencing present joys. Bird suggests three reasons for Jesus’ descent into Hades:

In light of both interpretations considered, I cannot see how this is an either/or. When we confess Jesus' suffering on our behalf, we do confess that he suffered the torments and punishment for sin to the degree that he, the sinless and perfect Son of God, felt the effects of hell on our behalf. But Bird also makes a biblical case that there was more to Jesus’ death than merely this. It was a declaration of victory over the powers of Satan and his emissaries, and indeed a triumph on behalf of us, his people. Both are compatible with our previous study on the atonement: it was both for our sin and victory over Satan on our behalf! Conclusion The descent of Jesus into hell is a rather obscure doctrine in the Christian church, upon which many faithful believers are divided. At this point it is important to point out that there is no salvific merit in this article, and therefore there must be much grace shown with different parties who disagree on this matter. There is one position, however, that claims that Jesus descended into hell to seemingly pay a ransom to Satan, and then through a slight of hand defeats the unexpected foe. This position must be rejected as heretical. There is no evidence of Jesus ever having to make payment to Satan for our sins, or that God used deception to outwit Satan! Jesus conquers Satan, he doesn’t pay it. Michael Horton clarifies, “The curse of sin and death was a sentence imposed by God for the violation of his law; Satan’s role in the drama is that of seducer and prosecutor rather than judge or claimant in dispute. The truth in this conception is that God outwitted Satan and the rulers of this age by triumphing over them precisely where they celebrated God’s defeat.”[14] This is what was captured eloquently by Lewis in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, which we quoted last week in conclusion to our study. Just because Satan doesn’t understand God’s designs, doesn’t mean that it was deceived. The article of Jesus’ descent into hell is both the extent to which Jesus carried our penalty (Calvin’s view) and the victory over Satan on our behalf (Bird). Both are true in light of what the Creed affirms in this article, and rich in meaning for the believer. Through this those who trust in the atoning sacrifice of Christ can be sure that he bore our full punishment in himself, and through this conquered the powers of darkness on our behalf. This is a comforting article in the Creed, and ought to cause us to glory in our Redeemer. Next week we will look at the second part to this article, and that is concerning Jesus' resurrection from the dead, which I titled "Jesus' victory over death." [1] I have kept the traditional wording “hell” rather than the new versions “into the place of the dead” for the sake of interest. We must now explain what is meant by “hell”. [2] I initially started writing this as an entirety, but realised that it needed two sessions to cover it all in depth. [3] Heidelberg Catechism, Q44. [4] See Packer, J.I. 1994. Growing in Christ. Wheaton: Crossway Books, pg. 56. [5] See Calvin, J. Institutes of the Christian Religion. II:XVI:8: “Now it appears from ancient writers that this phrase which we read in the Creed was once not so much used in the churches… From this we may conjecture that it was inserted after a time, and did not become customary in the churches at once, but gradually.” (in Battles, F.L. transl. & McNeil, J.T. ed. 1960. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, pg. 512. [6] Aquinus, T. Summa Theologica. III: LII: 1. [7] Bird, M.F. 2016. What Christians Ought to Believe. Grand Rapids, Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 148. [8] Packer, J.I. 1994. Growing in Christ. Wheaton: Crossway Books, 56. [9] Bird, pg. 148. [10] Ibid, pg. 145. [11] He refers to Revelation 20:14 which states explicitly that “Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire.” [12] Ibid, pg. 144. [13] Ibid, pg. 145-146. [14] Horton, M. 2011. The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 501-502. Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance. Last week we saw how the church had come to affirm that in the one person we know as Jesus, he has two natures both united and bound in perfection, yet neither one diminishing the other. These two natures show us that Jesus is both fully human, as well as fully divine. We also saw that in relation to his human nature, he came to fulfil a messianic mission. In other words, the title given to him which we know as Christ literally is a anglicised version of the Greek translation of the Hebrew word Messiah. But what did this mission look like? The Creed tells us that Jesus “suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried.” The paradox of this confession is that it has come to mean victory, rather than defeat, in Christian tradition. But how can the suffering of an innocent Galilean preacher be, firstly victorious; and secondly, this being in fulfilment of the messianic expectation? This week we will look at how Jesus’ suffering brought about God’s decisive victory over the powers of darkness and evil, and especially how this provided for the platform of the greatest exodus in history: the redemption of God’s people from the bondage to sin. No Gospel without Suffering When the Creed affirms that Jesus “suffered under Pontius Pilate,” it is affirming a real historical event that involved real people. This is a great declaration of the actual death of Jesus, the Jewish preacher from Galilee. This is an important point because of what the Creed affirms about the nature of Jesus’ death, that it was suffering. What does this mean? It has been commonly said “that the Gospels are passion narratives with long introductions.”[1] In other words, while the Gospels certainly give us some details concerning Jesus’ life, a bit more about his ministry, they are particularly interested in the last week of his life that leads up to his death. This is because of the central role that Jesus’ death came to play in his own mission, as well as in the life of the church. In a very real sense, Jesus came to suffer and die. Three times in Luke Jesus foretells of his own death (9:21-22, 43-45; 18:31-34). A third of Mark is devoted to the final week of Jesus’ life, and devotes a significant portion of this to his suffering, death, and burial. So too, Matthew spends much time preparing the reader for the climactic moment of Jesus’ death beginning with the plot by the religious leaders to kill Jesus (26:1-5); followed by an anointing ceremony scene which Jesus says is in preparation for his burial (26:12); with this leading to the description of Judas’ betrayal (26:14-16); and climaxing with Jesus’ Passover meal with his own disciples, interpreting the elements in sacrificial terms and relating this to an institution of a new covenant that will be ratified by his own blood (26:28). We can therefore see from the gospel authors’ own narratives, that there is no gospel (i.e. good news) without the suffering and death of Jesus. But why is this so? Why did the suffering that Jesus undertook to accomplish in Jerusalem become the basis for the proclamation of the good news of the early church? There are two major answers given to this in the history of the church. Jesus and the Victory of God[2] A very early understanding of Jesus’ death which has found a resurgence in Christian theology is the conquering of the cosmic powers through the death of the Christ on the Cross.[3] This narrative begins in Genesis 3:15 with the promise that the seed of the woman would crush the head of the serpent. One can say, since the garden experience of our first parents, the Serpent’s intention is to destroy the image of God reflected in the image bearing creatures of God, humanity. And since our first parents failed to withstand the evil intention of the Serpent and destroy it in the garden, their offspring now born into a world of suffering and shame are perpetually tormented by the evil that seeks to oppose God and his design. We as humans are thus held in bondage to the cosmic powers, and are powerless against its attacks. It was, therefore, for this reason that God had to take on flesh and become a human being in order to suffer on our behalf and conquer Satan and his emissaries as a human being. In a very real sense, therefore, God took on flesh in the person of Jesus Christ as a plan from before the foundations of the earth to redeem mankind from the powers of darkness Scripture is very clear that the people of God are opposed by an enemy. We see this in Genesis 3 with the Serpent coming against the woman and causing her and Adam to fall into corruption, we see this in the account of Job, and some cryptic passages Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel, and then in the cosmic battle scene in Revelation 12. But also in passages such as 1 Peter 5:8 where Peter writes, “Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour.” Therefore we see in the ministry of Jesus that he came to oppose the forces of darkness when the gospels record his temptation narratives (Matthew 4:1-11; Luke 4:1-13) and his casting out of demons (Mark 1:21-28, etc.). Furthermore, the authors of the New Testament explicitly stated that this was one of the reasons Jesus came: to destroy the works of the devil (1 John 3:8). But we also know from Scripture that often the means Satan uses to oppose the people of God are corrupt political entities and even the good intents of people. We see this very clearly in the account of Egypt and Israel’s bondage to her, with God coming to rescue her through Moses and the series of plagues being a judgment upon the spiritual darkness that rules over Egypt; also we see this with Babylon and Israel’s exile, with Babylon becoming a metaphor in Revelation for the Roman Empire which stands in opposition to the floundering church. The concept of the Antichrist of 1 John 2:18 and the woman who is drunk with the blood of the saints in Revelation 17:6 are all examples of large powers coming under the influence of Satan and opposing God’s people. Furthermore, we see individuals coming under the influence to serve the purposes of Satan in Judas Iscariot, when the gospels report that Satan entered Judas to betray Jesus (Luke 22:3), or even that the good intentions of Peter attempting to prevent Jesus from going to the cross was seen as Peter, in that moment, serving the purposes of Satan (Matthew 16:23). Furthermore, the Pharisees are called the sons of the devil by Jesus in John 8:44. In this sense, the influence of Satan has infiltrated every sphere of human existence, and thus it was necessary that it be defeated by One who was more powerful than it, since humanity is unable to do so on its own. But why through suffering? Could God not overthrow Satan by pure force? Why did Jesus have to suffer? Jesus and the Victims of Sin We have just seen that we have an enemy that opposes us from without, but we also have an enemy that opposes us from within: sin. Ever since our first parents fell into sin, they brought distortion to every part of creation into what was an otherwise perfect paradise. Theologians have called this original sin, which means that every person born into this world is born with an already sinful disposition. In other words, we cannot but help to sin because sin has affected every part of our being. This means that though we still reflect the image of a beautiful and glorious God (Genesis 1:26-27), this image is now distorted. As a result, our rational faculties, our emotional faculties, our sexual appetites, everything is distorted by sin. Even our motivations are distorted, resulting in our even doing good out of impure desires. This doesn’t mean that people cannot do good deeds, since people still bear the image of God which enables them to reflect some of his characteristics into the world (such as fighting for justice, being merciful, loving others, etc.). However, the problem is that because of the fall into sin, even our good deeds are tainted by corruption, and are thus distorted. And the greatest distortion is our relationship to God himself, from whom we are now estranged because of the Fall. Because of this, our lives that were to be devoted to His glory, are now lived for our own, even if it’s for our collective selves as humanity (see Babel in Genesis 11). So while we may seek the good of others, the problem is that we may now seek the good of humanity over and above the good that God requires of us. And for this reason, our good works are rendered insufficient for reaching God, in fact, they might drive a further wedge between us and Him since we may think that our good deeds toward others are sufficient in themselves for our own salvation. People talk like this all the time, “I am a good person, so why should God not approve of me?” But what if what you consider to be “good” is insufficient? How would you know this if your own ability to reason and see clearly is clouded by your own judgment that is, in a large part, distorted? Therefore, what we need most is an objective standard given from without by which we can measure ourselves, not created from within. We need a higher law, a greater good. And this is what was given to our first parents in the garden and later reflected in the 10 commandments. It was this standard that was transgressed, bringing death and destruction to the world where there was once goodness, beauty, and truth. This is why the punishment for transgression of this initial law was death (Genesis 2:16-17), because it brought death into a world where only life existed, transgressing the law of life itself. The only solution to the plight of man now was for mankind to suffer death or atone for the transgression, but there was no man who could pay the debt since all men were now born into corruption and death, and are tainted by the Fall and distorted in our various passions as image bearers (see Romans 3:9-23). What was now necessary was for one from outside to offer up the penalty for sin and death, and this outsider had to be both perfect as well as man. It was for this reason that God, the lawgiver, took on flesh and became man, to pay the penalty for mankind. This is why Paul wrote in Galatians 4:4-5, “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons.” In other words, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us…” (Galatians 2:13). And since we are guilty by virtue of our first parents in the garden, there is one requirement required on our part in order to receive this free gift offered in the death of Christ: we must acknowledge our guilt and place our trust in Him by faith. For when we measure ourselves by the objective law of God given from without, we realise that we fall far short of God’s glorious standard (Romans 3:23) and need redemption. This is no trivial requirement, for in acknowledging our guilt we also acknowledge our need for deliverance. This is a humbling act that places God back on the throne and us as his subjects. It moves us away from the thought that we can make things right ourselves by our own good deeds, and acknowledges that we need grace from without. We thus come to God humbly and needy. For this reason Paul wrote in Galatians 2:16, “yet we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified.” In other words, Jesus suffered the death that we deserved under the law, in order that through his suffering and death he may justify (i.e. declare to be in the right) those who trust in his sacrifice on our behalf. Peter writes remarkably, “For Christ suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God…” (1 Peter 3:18). In this sense, Jesus redeems all those who have fallen victim to sin and recognise that they need deliverance and so cry out to God for help. Calvin writes, “For because God was provoked to wrath by man’s disobedience, by Christ’s own obedience he wiped out ours, showing himself obedient to his Father even unto death. And by his death he offered himself as a sacrifice to his Father, in order that his justice might once for all be appeased for all time, in order that believers might be eternally sanctified, in order that the eternal satisfaction might be fulfilled. He poured out his sacred blood in payment for our redemption, in order that God’s anger, kindled against us, might be extinguished and our iniquity might be cleansed.”[4] Conclusion: The Paradox of Strength through Suffering[5] In concluding, it is important to understand why the Messiah had to suffer and die. As we saw above, he came to defeat the cosmic powers of evil and injustice. But he also came to atone for the sins of mankind and to bring restitution between God and man by giving up his own perfect body in payment for the death that man deserves. In other words, he came to save us from both Satan and the justice of God required in the law. The mystery of the defeat of the cosmic powers in the suffering of Jesus and his atoning sacrifice on behalf of sinners is remarkable. C.S. Lewis captures the paradox well in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, when Aslan explains to the two young girls the mystery of the atonement as defeat of evil and payment for the guilty, “‘It means,’ said Aslan, ‘that though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of time. But if she could have looked a little further back, into the stillness and the darkness before Time dawned, she would have read there a different incantation. She would have known that a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backwards.”[6] Lewis, in literary form, attempts to capture the mystery of both the defeat of Satan and the atoning sacrifice on behalf of believers in the death of Christ, which Paul describes in Colossians 2:13-15 in this way, “And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses, by cancelling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross. He disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, by triumphing over them in him.” This is why the Creed affirms the suffering and death of Christ. He suffered on our behalf, and died a death we could not die, and through the weakness of the cross he triumphed over the powers of evil and delivered us from our bondage to these powers that enslaved us. This is the significance of the atonement, and the mystery of the power in the cross of Christ displayed through weakness, the greatest paradox in history. Therefore the suffering and death of Jesus is Gospel, or in other words, good news to the Christian. It reminds us that the power of God is not the power of mankind, and the mystery of the gospel is that the suffering of the Son of God on behalf of mankind has brought about the deliverance of many from both Satan and sin. Through his suffering we are set free, and are now able to glorify God as we ought to with our entire lives. Soli Deo Gloria. [1] Horton, M. 2011. The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims On the Way. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 492. [2] See Alen, G. 1953. Christus Victor (trans. Herbert, A.G.). London: S.P.C.K. & Wright, N.T. 2006. Evil and the Justice of God. London: S.P.C.K. for two excellent modern treatments of this position. [3] See Horton, M. 2011. The Christian Faith, pg. 502ff. [4] Calvin, J. Catechism: [5] Martin Luther called this a theology of the cross. See this article by Carl Truman for an excellent explanation on this theology: http://www.opc.org/new_horizons/NH05/10b.html [6] Lewis, C.S. 1950. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. London: Harper Collins, pg. 148. Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance.  A few weeks back we saw that within the first four centuries of Christianity, the questions about who Jesus was came to the fore in various discussions concerning, firstly his humanity, and then secondly his deity. One of the predominant questions that faced Christians in the late first and early second centuries were whether Jesus was actually human, and then especially in the third century and fourth centuries, the question moved to whether or not Jesus was in fact God incarnate. From this we saw that the question which Jesus posed to his own disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” was just as relevant in the second, third, and fourth centuries as it was in his own day, and continues to be a relevant question for us in our own time. However, the next question that Jesus asked his disciples confronted them with the reality of his own person, and has confronted people right throughout the centuries, and continues to confront us today, “Who do you say that I am?” The question does not leave any room for neutrality regarding the man from Galilee named Jesus. So who exactly do Christians believe that Jesus is? The creed moves into the person of Christ by affirming, “I believe in Jesus Christ, God’s only Son, our Lord.” There are two main doctrines that this little statement affirms concerning the identity of Jesus which we will look at and discuss this week: (1) His humanity and his accompanying role in this; and (2) his deity and what this means for us as his subjects. I believe in Jesus Christ When the creed affirms, “I believe in Jesus Christ”, it is affirming that Jesus is the man who was born to Mary in Bethlehem, and was raised in Nazareth. In other words, it is affirming the real historical person who walked, talked, hungered, cried, grew and ate and drank in order to sustain his physical self. New Testament scholarship in the twentieth century has seen a great renewal in attempting to place Jesus within his own Jewish context.[1] While there have been many unhelpful things about this movement, such as those who attempt to discredit anything miraculous about Jesus’ life in favour of him being a mere ordinary itinerary preacher in Galilee, there have been many helpful things about it too. Firstly, it has reminded us that Jesus was born into a particular historical context, into a particular people group, during a particular political period. Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection must be understood in light of this complex period. It also shows us that Jesus’ teachings are better understood once we better understand the context into which Jesus spoke. Secondly, it reminds us that Jesus was fully human. While no one outright denies the humanity of Jesus, many people in the church find it very difficult to think of Jesus in human terms. He hungered at times, became thirsty, was weakened and wearied by labour and toil. In other words, Jesus was assuredly a human being like you and I, with one distinct difference, he remained untainted by our sinful nature. But Jesus was nonetheless fully human. For this reason, as the author to the Hebrews reminds us, Jesus can sympathise with our weakness (Hebrews 4:15). N.T. Wright says it well when he writes, “The point of having Jesus at the centre of a religion or a faith is that one has Jesus: not a cypher, a strange silhouetted Christ-figure, nor yet an icon, but the one Jesus the New Testament writers know, the one born in Palestine in the reign of Augustus Caesar, and crucified outside Jerusalem in the reign of his successor Tiberius. Christianity appeals to history; to history it must go.”[2] But who is this Jesus? The creed affirms that he is the Christ. Now, for many people, this term is lost and they might think that “Christ” is simply Jesus’ surname, as if his parents were called Joseph Christ and Mary Christ. But “Christ” is not a surname at all, but rather the anglicised version of the Greek rendering of Messiah. In other words, it is a title, and this title is tied very much to Jesus’ earthly identity and his mission in a few distinct ways. Firstly, the “Messiah” is a very Jewish concept. It simply means “anointed one”, and often refers to the kingly lineage of the Davidic line in Biblical literature.[3] But it also came to reflect the anticipated hope of a prophesied deliverer who would come and deliver Israel from suffering and injustice and rule as a priest/king upon the throne of David establishing and everlasting dynasty.[4] Though the messianic concept was by no means monolithic in the first century, there were certain elements that were agreed upon which the Messiah had to fulfil.[5]

It is therefore no strange thing that John Calvin came to develop these three offices of Prophet, Priest, and King in light of what Jesus revealed about himself.[7] Calvin wrote, “As I have elsewhere shown, I recognize that Christ was called Messiah especially with respect to, and by virtue of, his kingship. Yet his anointings as prophet and as priest have their place and must not be overlooked by us.”[8] Jesus fulfilled the Messianic identity by fulfilling all three of the Israelite offices of Prophet, Priest, and King. I believe that Jesus is God’s Son, our Lord. But if the Messiah is closely tied to his earthly identity and mission, then the Greek translated “Lord” must be seen as relating to his heavenly identity as the Son of God. The first thing we must note, before we move into any discussions concerning the deity of Jesus as God’s Son, is the question whether or not the title “son of God” necessarily implies divinity. It is true that in the Bible this title is not uniquely ascribed to Jesus alone. The Bible calls Adam God’s son (Luke 3:38), Israel God’s son (Exodus 4:22), the angels are referred to as the sons of God (see Genesis 6:1-3, Job 1:6; 2:1), and Christian believers are referred to as “sons of God” (Romans 8:14). Does this mean that all of these have divine status? No, certainly not. Mogens Müller writes, “The Hebrew… and Aramaic [word for] ‘son,’ designate not only a male descendent but also a relationship to a community, a country, a species… ‘Son of God’ can thus mean both a… figure of divine origin, a being belonging to the divine sphere (such as an angel), or a human being having a special relationship to a god.”[9] However, “In the New Testament, Son of God… is a title often used in Christological confessions.”[10] In other words, when applied to Jesus in the New Testament, the term “Son of God” came to mean something quite different from the ordinary use ascribed to Adam, Israel, or angels. For example, in Mark’s gospel, his purpose for writing is to write about “the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1), and throughout the gospel at pivotal moments he seeks to demonstrate just how Jesus is this unique Son of God. For example, the voice from heaven in Mark 1:11 at Jesus’ baptism, “You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased”; or at the transfiguration when a voice from heaven once again declares, “This is my beloved Son; listen to him” (Mark 9:7); or the confession of the Roman Centurion at Jesus’ crucifixion when Mark records, “And when the centurion, who stood facing him, saw that in this way he breathed his last, he said, ‘Truly this man was the Son of God’” (Mark 15:39). John’s gospel connects the title with the ontological[11] reality of who Jesus is when he opens his gospel with, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1), and then John continues in verse 14, “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.” In this sense the way in which the early Christians came to see Jesus as the Son of God was in a unique relationship that separated him from everyone else who is called the son or sons of God in Scripture. This is why the New Testament authors used a technical term monogenes, which technically means “unique” or “having no equal”, often translated as begotten. Some translators have tried to emphasise this term by explaining Jesus as “the one-of-a-kind Son.” Believers are sons of God by adoption, but Jesus is God’s only Son, and not in the sense of decent, but rather in the sense of essence. Jesus, though he is in his incarnation fully human, he is in his essence fully God. This is further elaborated by the creed including that Jesus is “our Lord.”[12] If Jesus is in fact divine, one would expect that the New Testament authors ascribed to him a position that belongs to God alone, and this comes through very clearly by calling him Lord. This is, after all, the point of the hymn in Philippians 2:9-11 when Paul writes, “God has highly exalted him and bestowed upon him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” Furthermore, Mark’s quotation from Isaiah 40:3 ascribes to Jesus a text that was clearly a reference to YHWH coming back to Jerusalem when he quotes, “Behold, I send my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way, the voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.’” Donald Hagner comments on this passage, “Another expression in Mark is kyrios [Lord], which can mean ‘sir,’ but also can be a divine title referring to a sovereign ruler. Implicitly, the latter is the sense of the word as it is used in 1:3…”[13] There are a plethora of passages which describe Jesus as Lord in a way that can only refer to his divinity in the New Testament, texts that ascribe to Jesus that which belonged only to YHWH in the Old Testament, or that spoke explicitly of YHWH and was now applied to Jesus himself. But the question is, how do we balance the humanity and deity of Jesus in one person? And this was the challenge of the early Christian discussion concerning the first four centuries of Christendom, and finally was established as the doctrine of the Two Natures of Christ. Conclusion: The Two Natures of Christ. Holding in perfect balance both the humanity and the deity of Jesus has been one of the great challenges of Christianity, and still to a large degree remains a mystery to us. However, Christian theologians have grappled with this question. For the early apostolic preaching, Jesus’ humanity and divinity was assumed. But since heretical sects came to emphasize either one or the other, the church had to give a definitive answer as to this seeming conundrum. Michael Bird summarises the doctrine when he writes, “the view that won the day was that Jesus had two natures – divine and human – which were united but unmixed in his one person. This view is called hypostatic union and was formally ratified by the church at the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451). The basic thrust of the Council was to affirm that Christ possesses everything true of a person and he possesses everything true of both the human and the divine natures.”[14] In other words, the eternal person of the Son, whom John calls “The Word” (John 1:1), and who Jesus said existed with the Father “before the world existed” (John 17:5), this person possesses a divine nature that is eternal, and it was this person that “became flesh and dwelt among us,” and in his taking on flesh he also took on a second nature, namely a human nature, and therefore the person of the Son, the eternal Word, now had two natures, both divine and human, without the one diminishing the other. Both natures, therefore, exist in the one Person. This is Jesus Christ, the Son of God, our Lord. [1] N. T. Wright, 1996. Jesus and the Victory of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pg. 5. [2] Ibid, pg. 11. [3] Sawyer, J. F. A. 1993. Messiah (in Metzger, B. M. & Coogan, M. D. eds. The Oxford Companion of the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press), pg. 513ff. [4] Ibid. [5] See http://ntwrightpage.com/2016/04/05/jesus/ [6] Ibid. [7] See Calvin, J: II:XV:I-VI. [8] Calvin, J. 1559. II:XV:II (transl. Battles, F. L. & McNeill, J.T. ed. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion Vol. 1. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press). [9] Müller, M. 1993. Son of God (in Metzger, B. M. & Coogan, M. D. eds. The Oxford Companion of the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press), pg. 710. [10] Ibid. [11] Ontological: in other words, as he is in himself at the core of his being. [12] See Pannenberg, W. The Apostle’s Creed In Light of Today’s Questions. London: SCM Press Ltd, pg. 68, “That as the Son of God Jesus belongs to the essence of God himself is also brought out through the term ‘Lord.’” [13] Hagner, D. A. 2012. The New Testament: A Historical and Theological Introduction. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, pg. 172f. [14] Bird, M. F. 2016. What Christians Ought To Believe. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 82. Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance. The Gospel according to Mark records possibly one of the most significant questions that Jesus ever asked his disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” This question has received as many responses throughout history as it did in the first century when it was asked, “John the Baptist; and others say, Elijah; and others, one of the prophets.” In our own time, people herald Jesus as a great teacher, on par with Ghandi and Buddha; or one of the great prophets, such as Islam teaches; even in Jewish scholarship there has been a great revival in seeing Jesus as one of the great teachers of Israel.[1] But then Jesus asked his disciples a second question, “But who do you say that I am?” And it is upon the answer given to this question that the entire Christian faith hinges. Here truly, as we would say in South Africa, “the tekkie hits the tar.”[2] Mark simply records Peter as declaring, “You are the Christ,” while Matthew adds, “the Son of the living God.” The next article of the creed deals with what we call Christology. Last time we did a short summary of the doctrine of God, concluding the first article of the Apostle’s Creed, and this week we shall give a short introduction to the second article of the Apostle’s Creed. In one sense, I would like to present the question Jesus asked to his disciples again, looking at the questions that faced the early Christians through the first four centuries, and hopefully introduce the question that we will be spending the next term on in a manner that piques your interest in the question afresh again. So, who do people say that Jesus is? Is Jesus Human? What many people don’t realise, is that one of the main questions toward the end of the first century and into the second century revolved around Jesus’ humanity. We can already see hints of this combatted in the questions which John addresses in his gospel and epistles, “For many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess the coming of Jesus Christ in the flesh” (2 John 7). This is why John emphasized, "That… which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and have touched with our hands…” (1 John 1:1). Two early heresies were combatted by the use of such texts and eyewitness accounts of the apostles: Docetism and Gnosticism. Docetism: Jesus only appeared human. Possibly one of the first early heresies, and likely the heresy combatted by John in his letters, is what has come to be called Docetism. The term Docetism is derived from the Greek word dokein which means “to seem”.[3] In this early position, those who taught this believed that Jesus did not come in the flesh, but rather seemed as though he had. The problems with this position can be discerned quite easily. If Jesus wasn’t actually human, and only an apparition of humanity, then his death did not accomplish anything, for he did not shed real blood for real sin. In this sense, it was absolutely important for those, such as John, who may have come into contact with some of these teachings to emphasize the true humanity of Jesus. This is why John employs all five of the sense when he describes his own experience of Christ, the one who was heard, seen, looked upon, and especially touched. Jesus was fully human and therefore shed real blood, and thus the blood he shed is sufficient for the cleansing of real sin. Gnosticism: Jesus came to impart secret knowledge. Possibly growing out of Docetism was the ancient heresy of Gnosticism, which has found a great resurgence in modern times with the discovery of many Gnostic texts at Nag Hammadi, Egypt. Thanks to this discovery, we can now understand very clearly what early church fathers such as Irenaeus was up against when he published his Against Heresies. Gnosticism was prevalent during the second century after Christ, and became popular through the circulation of alternate gospels called Gnostic Gospels, which portrayed Jesus as a heavenly figure who came down out of heaven to impart secret teachings to a select group of people who would accept this gnosis (secret knowledge), and by this knowledge be able to escape this wicked physical world and transcend to a spiritual abode in the heavens. For these gnostics, the man Jesus was not as important as the person Christ, who was the authentic teacher and saviour. One of the famous gnostic gospels to have been discovered in recent years is the Gospel of Judas, which portrays Judas as a hero who is the only one who understands the message of the Christ, and to whom the Christ has imparted secret knowledge. This knowledge is the reality that the Christ must escape the trappings of the physical body of Jesus, and Judas will be the means of escape by betraying him, which will lead to his eventual death. By this act, Judas becomes the hero and the only one to understand the divine language, showing himself to have the spark of divinity in himself which will lead to his deliverance from the trappings of his body. Gnostic teachings considered the physical body to be evil, and the spirit to be good, and so true salvation happened when we escaped the physical world and were taken up into the spiritual. Gnostic gospels, such as the Gospel of Thomas and Judas, contained many so called secret teachings of Jesus which, if grasped, brought about a spiritual salvation from the physical world, rather than redemption from sin. Jesus, the man we confess. So when the Creed affirms, “I believe in Jesus,” the use of Jesus’ actual name is affirming his full humanity, and is a very significant point of confession late in the second century when the Creed was first used, for these heresies flourished during this period. Early Christian orthodoxy affirmed the full humanity of Christ, and so affirmed his real suffering and actual death, and therefore the blood of Christ that was shed was his blood. Furthermore, the creed also affirms the actual death of Jesus for the remission of sins, and will also affirm the resurrection of his physical body. This was in contradiction to the Gnostic teachers who merely affirmed his teaching role as imparting mystical meaning in order to escape the physical world, and they certainly did not affirm his physical resurrection from the dead, but rather only his spiritual resurrection. This idea has resurfaced among scholars such as Marcus Borg who denies the physical resurrection of Jesus, and argues that Jesus rose “in the hearts of his disciples.”[4] Now, while Borg will by no means say that he is a Gnostic teacher, the reality is that his denial of the physical resurrection of Jesus places him in the same camp as them. Jesus thus becomes the “Lord” through his teaching, and is present only in a mystical sense. But the early disciples and apostles, as well as those who followed them, were convinced on the point that Jesus actually rose physically from the dead, and it was on this point that the gospel was based (see 1 Corinthians 15).[5] The creed affirms what the early apostolic church taught, and that was Jesus’ full humanity, his actual suffering on behalf of sin, and his physical resurrection from the dead. Is Jesus God? The battle over Jesus’ humanity was won already by the fourth century, and since then it has not become a major dispute. Apart perhaps from some fringe ecstatic groups through the centuries, no one denies that Jesus was an actual person who walked, talked, ate, and lived in Palestine during the first century. But starting in the late third to early fourth centuries, the question over Jesus’ divinity became of central concern, and this has lasted even into our own time. Now, while the Apostle’s Creed didn’t necessarily deal with this question primarily, it certainly did affirm the nature of Jesus as God’s “only Son,” and as with early Christian affirmation this is an affirmation of his eternal nature as divine. But how exactly is Jesus God’s Son? This became the focus of discussions during the third and fourth centuries as people tried to reconcile the evidence of Jesus’ own identity as the eternal Word made flesh (John 1:14) and his humanity. Two problems occurred that tried to reconcile these two. Adoptionism: Jesus is adopted by God. This early view which found it’s root possibly in the late second century, but came to full bloom in the third century, taught that “Jesus was merely an ordinary man of unusual virtue or closeness to God whom God ‘adopted’ into the divine Sonship.”[6] It taught that the man Jesus was adopted when the Christ or Logos came upon him through the Spirit either at his baptism, or when he was declared to be the Son of God at his resurrection. It was here that upon the ordinary man Jesus divine status was conferred. Wayne Grudem writes, “Many modern people who think of Jesus as a great man and someone especially empowered by God, but not really divine, would fall into the adoptionist category.”[7] The problem with adoptionism is that it doesn’t take into account the apostolic teaching about the pre-existence of the Word (logos) which, as John wrote, “was with God, and was God” (John 1:1). John continues and writes that not only was the Word from the beginning, echoing Genesis 1:1, but that “all things were made through him.” This very Word “became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). Or even the author to the Hebrews who writes in 1:2 that the Son was the one “through whom also [God] created the world,” and then goes on to speak of the person of Jesus, as a result, being greater than Moses and even the angels. Furthermore, the fact that this Jesus was conceived of the Holy Spirit in the womb of the virgin Mary shows that his coming into this world is supernatural, and that though the Spirit came upon him at his baptism, this was not to say that this is the first time the Spirit was with him. The great hymn of Philippians 2 speaks of Jesus being in the form of God prior to his incarnation, and then speaks of his incarnation as his humbling himself to the place of a servant. Paul also speaks of Jesus’ pre-eminence through whom all things were created and for him (Colossians 2:16). So from this early apostolic record we can see that there was no indication that the early witness about Jesus contained any notion of adoptionism. Therefore this view did not take root. Arianism: Jesus is an exalted creature. The large battle was the Arian controversy in the fourth century, and is still prevalent today among the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Arius was an Alexandrian preacher who argued for a hierarchical order within the divine economy, of whom the Father was the only one who is fully divine.[8] Michael Bird summarises his position, “So on Arius’s view, Jesus was a created being, the greatest created being by all accounts, but still a creature nonetheless.” For Arius, Jesus was in fact greater than the angels as the author of Hebrews argues, and through whom all else was created, because, arguing from Colossians 1:15, he said that the Son was “the firstborn of all creation,” and by this he understood that the Son was not the eternal Word of John 1, but rather the first creature to be created above all other creatures. So the Son did exist from the beginning, but not from before the beginning. The church father, Athanasius, stood firmly against Arius, and at one time seemed to be the only one to stand against this controversy. There is a phrase in Latin ascribed to Athanasius which states, “Athanasius contra mundum,” which literally means, “Athanasius against the world.” Athanasius’ critique against Arius pointed out the impossibility for a creature, even a sinless creature, to pay the eternal debt of another creature's sin against the holy and righteous eternal God of heaven and earth. The sacrifice, if it needed to be once off for all eternity, had to be from an eternal being, and so it was necessary for God to become incarnate in Jesus in order to pay the debt on our behalf.[9] Secondly, the plethora of passages that ascribes worship to Jesus which belongs to God alone was another devastating argument, because, as Bird points out, “The worship of an angel or even a super angel would be idolatrous and blasphemous because no one but God is worthy of the church’s worship.”[10] And finally, the Jews had Jesus executed because they certainly understood that Jesus was making himself equal with God, not subordinated as a creature, even a highly exalted creature. Jesus was vindicated at his own resurrection, showing that the power of death could not hold him since he was no mere creature. Conclusion As we can see, the question Jesus has asked his own disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” has been a question of contention right throughout history, and remains so even in our own time. The difference between answering that Jesus is either a prophet, an exalted creature, a wise sage imparting secret knowledge, or God incarnate, is huge. C.S. Lewis' categories of liar, lunatic, or Lord still remains. Jesus was either a liar, a lunatic, or he is Lord. Either Christians worship an idol, or everyone who is not a Christian is worshipping something that is entirely false. The question Jesus posed, “Who do you say that I am?” remains one of the most important questions that you and I may face in this life. Christians are convinced that eternity hinges upon this very question. Over the course of the next term, we are going to be looking at what The Apostle’s Creed affirms about the nature of Jesus’ identity, and we are going to attempt to answer the question in light of what we believe the Bible teaches about who Jesus is. I encourage you, regardless of how you answer the question at present, to continue reading and thinking, and allow the question that Jesus posed to his disciples almost two thousand years ago to confront you in our own time. Who is Jesus for you? Is he a prophet, a wise sage, or is he, as Peter said, “The Christ, the Son of the living God”? [1] See this article by Craig Evans on the identify of Jesus in the ancient world and modern scholarship:http://www.craigaevans.com/Holmen-Porter_vol-2_13_Evans.pdf [2] A “tekkie” is slang in South Africa for running shoes. [3] McDonald, H.D. 1988. Docetism (in Ferguson, S. B. et al eds. 1988. New Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids: Intervarsity Press), pg. 201. [4] See Marcus Borg’s article: http://www.marcusjborg.com/2011/05/16/the-resurrection-of-jesus/ [5] For an excellent defence of the physical resurrection of Jesus, see: Wright, N. T. 2003. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [6] Kearsley, R. 1988. Adoptionism (in Ferguson, S. B. et al eds. 1988. New Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids: Intervarsity Press), 6. [7] Grudem, W. 1994. Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids: Inter-Varsity Press, pg. 245. [8] Bird, M. F. 2016. What Christians Ought To Believe. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 80. [9] See Athanasius, On the Incarnation of the Word. [10] Bird, pg. 81. Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance. If you have ever thought, “Why are there so many religions out there?” Or, what is the difference between the God of Christianity and the gods of Hinduism, or why it is that the various “holy books” portray such a vast difference in their understanding of God than that of the Bible, I believe the answer lies simply in the way people understand God in relation to two theological terms: transcendence and immanence. If you have ever wondered if theological jargon has any use, I hope that after reading this, you may come to see that theological language has an important role to play in our definitions when speaking of God. In my opinion, many errors both within the church as well as within religion in general comes as a result of a misunderstanding, and therefore a misapplication, of the doctrine of God’s transcendence, as well as His immanence. But what exactly do we mean by these terms? Before we go into each term as it relates to God, let us first define what we mean by transcendence and immanence. Michael Horton defines transcendence as “being entirely above and outside of creation”, and he defines immanence as “being entirely within creation.”[1] In other words, if we say that God is transcendent, we mean that he is entirely “above and outside of creation,” and if we say that God is immanent, we mean that he is “entirely within creation.” And so it is easy to see just how these two seemingly contradictory terms can cause a problem for our understanding of God, unless they are held in perfect balance. The Biblical understanding of God holds these two seemingly opposed emphases in balance. But how? We will therefore have to define both in relation to God as he is revealed in the Bible, and also see how different philosophies and religions emphasize one or the other, and the implications thereof. The God Who Is Transcendent When Genesis 1:1 opens up with the words, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” it seeks to emphasise the fact that God is completely distinct from the universe which he created. In other words, by implication, there was a time when the universe was not, but there was never a time when God was not, because time only exists within a material universe.[2] God is entirely outside of the material universe, and therefore outside of time. In this sense the question, “Who created God?” falls entirely flat, because God by definition in order to be God is entirely uncreated, eternal, and transcendent. Now, many religions and philosophical ideas emphasize God’s transcendence and teach that because God (if such a being even exists) is transcendent, he is both unknowable as well as completely uninvolved within the world, or in other words, entirely impersonal. One such understanding is deism, particularly popular in the 18th and 19th centuries: “deism involves belief in a creator who has established the universe and its processes but does not respond to human prayer or need.”[3] Another philosophical position, which can in a way be attributed to a radical transcendence of God, is agnosticism, which is the belief that in the absence of evidence, one cannot know if there is a god or not. If one exists, he is unknowable. Another system which was very influential in religion was that derived by the Greek philosopher Plato, who also held to a radical transcendence of what he called the ultimate Good. The metaphysical dualism of Plato drove a wedge between the material world and, what Plato considered to be the “real” world from which we fell, which is beyond the material. Though Plato rejected atheism, there is no certainty as to whether or not he “believed in one god, or two, or more.”[4] The reason for this is though Plato “believed that a divine intelligence and purpose is at work in the universe”, he did not believe that this “intelligence” was personal or knowable in any way. In religion, Plato’s concept gave rise early Gnosticism, which attempted to merge Biblical teaching with Plato’s dualism. It drove a great distinction between the material world and the spiritual world, the former being evil and the latter being good, and taught that a spiritual saviour had descended to give us spiritual knowledge of how to escape the evil material world and ascend to the spiritual world above. It even drove a radical distinction between the God of the Old Testament and the God of the New, saying the former was evil and at war with the latter. The good God was transcendent and could only be known in a pure spiritual state outside of this creation. Gnostic gospels were popular during the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., when texts such as the Gospel of Judas were circulated opposing the canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Another religion that emphasises the radical transcendence of God is Islam, with Allah being entirely other and even unknowable personally. He interacts with the world through angels and spirits, who communicates his message to prophets, the final of these according to Muslims being Muhammad. One can only be obedient to Allah, not know him personally, and even the prayers that are prayed to him are done out of obedience, not necessarily relationship. Submission is the key concept for a Muslim, for Allah demands unquestioned obedience. Another example is in certain sectors of primitive African religion, where there exists the concept of a higher being which is mediated through the ancestors of particular tribes. While the higher being cannot be known in a personal capacity, and in some respects cannot know the people either, the mediation that happens through the ancestors is of incredible importance. Ancestors who have departed are thought to be in a spiritual state and can mediate between this god and the people, and bring good fortune or ill as a result. Therefore appeasing the ancestors in order to earn favour for crop growth and fertility is an important aspect of Traditional African Religion. While we can see that transcendence is a very Biblical concept, we have also noticed how the emphasis on transcendence alone can lead to a variety of incorrect concepts of God. For example, if God is only transcendent, then he cannot be known in a personal capacity, he remains uninvolved personally in the world, and there is no way of knowing who he is, or what he is, or if speaking of he or she or it is correct or not. But what happens when we emphasize immanence? The God Who Is Immanent Not only does Genesis speak of God’s transcendence, but Genesis 1:2 reads, “The earth was without form and void, and the darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.” This text clearly speaks of God’s immanence, that though he is completely distinct from his creation, he is nonetheless involved personally within it. The entire Bible shows God speaking directly to his people, first to Adam in the garden, then to Cain, to Noah, Abraham, Moses, etc. etc. The Bible portrays a God who is personal and intimate. He makes himself known to us especially by revealing himself in a way we can understand. Of course, in Christianity, Christians insist that God is most intimate in the person of Jesus, who we say is God in flesh, becoming one like us in order to communicate himself to us in a way we can understand. This doctrine of God’s immanence makes a radical distinction between the Bible and the Qu'ran, African Tradition Religions, and other religions which emphasize transcendence only. But immanence, if emphasised on its own, can also lead to gross distortions and error. For example, theologians such as Friedrich Schleirmacher emphasized God’s immanence to the point where God was no different from his creation. He was so involved in his creation that he became one with it. In this sense, God cannot be known in a personal way, only felt.[5] An overemphasis of immanence moves away from doctrinal conviction about God more to the experience of God. God becomes mysteriously shrouded in darkness and we can only behold him as one feels the sensation of mist upon the skin, though one cannot see the cloud itself. New Age religions and philosophies emphasizes this aspect of the divine as being part of the world, and mystical experience being a key to connect both with the divine in the world as well as the divinity within oneself. Pantheism, which literally means God is all things, and panentheism, which states that creation is contained within God and is included in the divine, is the logical conclusion of those who emphasize only God’s immanence. Many religious philosophies fall prey to this error, notably Buddhism and Hinduism, whose “god” and “gods” are merely symbols that teach us to follow a certain path in this life in order to attain eventual “enlightenment” or “liberation”[6] which is, in an analogy, being swallowed up by the universe as a drop dissolves in the ocean. In other words, it is becoming one with the One, which is the universe.[7] New Age philosophies with its understanding of the interconnectedness of creature and divine, connecting all living creatures, follows a similar philosophy, and reincarnation becomes a prominent theme for those still striving to be released into the universe.[8] A great amount of emphasis is placed on esoteric experience of the individual, doctrine is to be treated with great scepticism, and truth becomes entirely subjective. Once again, as with transcendence, we first showed that immanence is a Biblical concept. The God of the Bible, though he is completely distinct from his creation, is nonetheless personally involved within it, or in other words, he is immanent. However, when immanence is emphasized to the exclusion of transcendence, we find that errors such as pantheism or panentheism creep in, and this is even true for Christian theology. The Creator/creature distinction then becomes blurred, and experience becomes the dogma, though God himself remains unknowable apart from our personal experience. The question is, however, how can Christianity hold these two seemingly opposed doctrines about God in balance?[9] Conclusion: God as Transcendent and Immanent As we have seen above, the emphasis on either transcendence or immanence leads to distortions in our understanding of God. According to the Bible, God is both transcendent and immanent. Because we understand God to be transcendent, we avoid speculation as to his divine nature. There are many things we cannot know about God precisely because he is transcendent. Theologians have always emphasized that we cannot know God as he is in himself, or in other words, we cannot know all of him. Theologians have called this doctrine the incomprehensibility of God, meaning that “Neither in creation nor in re-creation does God reveal himself exhaustively.”[10] This does not mean that we cannot know anything about God, but just that we ought not to speculate beyond what he has made known about himself. Deuteronomy 29:29 is an important verse in light of this, “The secret things belong to the LORD our God, but that which has been revealed belong to us and our children forever.” Those who emphasize the transcendence of God are right in saying that unless God makes himself known, we can know nothing of him. However, as Christians we are convinced that God has made himself known, and we can know what he has revealed about himself because we have his revelation recorded for us in Scripture. And because we understand God to be immanent, we also know that he is personally involved in this world. Though he is not part of creation, his presence does permeate it. We say that God is omnipresent, meaning that he is present everywhere, and that is because he is Spirit (John 4:24; Psalm 139:7-12). But this in no way makes him either part of creation or within creation in the sense that he is limited to material existence, or depended upon it. However, what God’s immanence does teach us is that we can in fact have an authentic experience of God! But because it is held in balance with his transcendence, it is always on the basis of his revelation, and not on the basis of our experience alone. Holding the balance between transcendence and immanence therefore teaches us that there are certain things we can know about God we would otherwise not know if he didn’t reveal it to us, and on the basis of how he has revealed himself to us, we can have an authentic experience of God because he is also immanent, or in other words, personally involved in the world and interacts with his creatures. Christian dogma, therefore, allows us to experience God through worship in a manner that does not risk idolatry, which is one of the primary reasons that the creeds were written down, taught, and recited. We can therefore say, “I believe (personal experience) in God, the Father Almighty (immanent) creator of heaven and earth (transcendent).” Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance. [1] Horton, M. 2011. The Christian Faith. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 996, 1002.