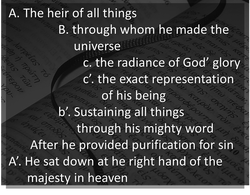

A few weeks back we saw that within the first four centuries of Christianity, the questions about who Jesus was came to the fore in various discussions concerning, firstly his humanity, and then secondly his deity. One of the predominant questions that faced Christians in the late first and early second centuries were whether Jesus was actually human, and then especially in the third century and fourth centuries, the question moved to whether or not Jesus was in fact God incarnate. From this we saw that the question which Jesus posed to his own disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” was just as relevant in the second, third, and fourth centuries as it was in his own day, and continues to be a relevant question for us in our own time. However, the next question that Jesus asked his disciples confronted them with the reality of his own person, and has confronted people right throughout the centuries, and continues to confront us today, “Who do you say that I am?” The question does not leave any room for neutrality regarding the man from Galilee named Jesus. So who exactly do Christians believe that Jesus is? The creed moves into the person of Christ by affirming, “I believe in Jesus Christ, God’s only Son, our Lord.” There are two main doctrines that this little statement affirms concerning the identity of Jesus which we will look at and discuss this week: (1) His humanity and his accompanying role in this; and (2) his deity and what this means for us as his subjects. I believe in Jesus Christ When the creed affirms, “I believe in Jesus Christ”, it is affirming that Jesus is the man who was born to Mary in Bethlehem, and was raised in Nazareth. In other words, it is affirming the real historical person who walked, talked, hungered, cried, grew and ate and drank in order to sustain his physical self. New Testament scholarship in the twentieth century has seen a great renewal in attempting to place Jesus within his own Jewish context.[1] While there have been many unhelpful things about this movement, such as those who attempt to discredit anything miraculous about Jesus’ life in favour of him being a mere ordinary itinerary preacher in Galilee, there have been many helpful things about it too. Firstly, it has reminded us that Jesus was born into a particular historical context, into a particular people group, during a particular political period. Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection must be understood in light of this complex period. It also shows us that Jesus’ teachings are better understood once we better understand the context into which Jesus spoke. Secondly, it reminds us that Jesus was fully human. While no one outright denies the humanity of Jesus, many people in the church find it very difficult to think of Jesus in human terms. He hungered at times, became thirsty, was weakened and wearied by labour and toil. In other words, Jesus was assuredly a human being like you and I, with one distinct difference, he remained untainted by our sinful nature. But Jesus was nonetheless fully human. For this reason, as the author to the Hebrews reminds us, Jesus can sympathise with our weakness (Hebrews 4:15). N.T. Wright says it well when he writes, “The point of having Jesus at the centre of a religion or a faith is that one has Jesus: not a cypher, a strange silhouetted Christ-figure, nor yet an icon, but the one Jesus the New Testament writers know, the one born in Palestine in the reign of Augustus Caesar, and crucified outside Jerusalem in the reign of his successor Tiberius. Christianity appeals to history; to history it must go.”[2] But who is this Jesus? The creed affirms that he is the Christ. Now, for many people, this term is lost and they might think that “Christ” is simply Jesus’ surname, as if his parents were called Joseph Christ and Mary Christ. But “Christ” is not a surname at all, but rather the anglicised version of the Greek rendering of Messiah. In other words, it is a title, and this title is tied very much to Jesus’ earthly identity and his mission in a few distinct ways. Firstly, the “Messiah” is a very Jewish concept. It simply means “anointed one”, and often refers to the kingly lineage of the Davidic line in Biblical literature.[3] But it also came to reflect the anticipated hope of a prophesied deliverer who would come and deliver Israel from suffering and injustice and rule as a priest/king upon the throne of David establishing and everlasting dynasty.[4] Though the messianic concept was by no means monolithic in the first century, there were certain elements that were agreed upon which the Messiah had to fulfil.[5]

It is therefore no strange thing that John Calvin came to develop these three offices of Prophet, Priest, and King in light of what Jesus revealed about himself.[7] Calvin wrote, “As I have elsewhere shown, I recognize that Christ was called Messiah especially with respect to, and by virtue of, his kingship. Yet his anointings as prophet and as priest have their place and must not be overlooked by us.”[8] Jesus fulfilled the Messianic identity by fulfilling all three of the Israelite offices of Prophet, Priest, and King. I believe that Jesus is God’s Son, our Lord. But if the Messiah is closely tied to his earthly identity and mission, then the Greek translated “Lord” must be seen as relating to his heavenly identity as the Son of God. The first thing we must note, before we move into any discussions concerning the deity of Jesus as God’s Son, is the question whether or not the title “son of God” necessarily implies divinity. It is true that in the Bible this title is not uniquely ascribed to Jesus alone. The Bible calls Adam God’s son (Luke 3:38), Israel God’s son (Exodus 4:22), the angels are referred to as the sons of God (see Genesis 6:1-3, Job 1:6; 2:1), and Christian believers are referred to as “sons of God” (Romans 8:14). Does this mean that all of these have divine status? No, certainly not. Mogens Müller writes, “The Hebrew… and Aramaic [word for] ‘son,’ designate not only a male descendent but also a relationship to a community, a country, a species… ‘Son of God’ can thus mean both a… figure of divine origin, a being belonging to the divine sphere (such as an angel), or a human being having a special relationship to a god.”[9] However, “In the New Testament, Son of God… is a title often used in Christological confessions.”[10] In other words, when applied to Jesus in the New Testament, the term “Son of God” came to mean something quite different from the ordinary use ascribed to Adam, Israel, or angels. For example, in Mark’s gospel, his purpose for writing is to write about “the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1), and throughout the gospel at pivotal moments he seeks to demonstrate just how Jesus is this unique Son of God. For example, the voice from heaven in Mark 1:11 at Jesus’ baptism, “You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased”; or at the transfiguration when a voice from heaven once again declares, “This is my beloved Son; listen to him” (Mark 9:7); or the confession of the Roman Centurion at Jesus’ crucifixion when Mark records, “And when the centurion, who stood facing him, saw that in this way he breathed his last, he said, ‘Truly this man was the Son of God’” (Mark 15:39). John’s gospel connects the title with the ontological[11] reality of who Jesus is when he opens his gospel with, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1), and then John continues in verse 14, “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.” In this sense the way in which the early Christians came to see Jesus as the Son of God was in a unique relationship that separated him from everyone else who is called the son or sons of God in Scripture. This is why the New Testament authors used a technical term monogenes, which technically means “unique” or “having no equal”, often translated as begotten. Some translators have tried to emphasise this term by explaining Jesus as “the one-of-a-kind Son.” Believers are sons of God by adoption, but Jesus is God’s only Son, and not in the sense of decent, but rather in the sense of essence. Jesus, though he is in his incarnation fully human, he is in his essence fully God. This is further elaborated by the creed including that Jesus is “our Lord.”[12] If Jesus is in fact divine, one would expect that the New Testament authors ascribed to him a position that belongs to God alone, and this comes through very clearly by calling him Lord. This is, after all, the point of the hymn in Philippians 2:9-11 when Paul writes, “God has highly exalted him and bestowed upon him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” Furthermore, Mark’s quotation from Isaiah 40:3 ascribes to Jesus a text that was clearly a reference to YHWH coming back to Jerusalem when he quotes, “Behold, I send my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way, the voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.’” Donald Hagner comments on this passage, “Another expression in Mark is kyrios [Lord], which can mean ‘sir,’ but also can be a divine title referring to a sovereign ruler. Implicitly, the latter is the sense of the word as it is used in 1:3…”[13] There are a plethora of passages which describe Jesus as Lord in a way that can only refer to his divinity in the New Testament, texts that ascribe to Jesus that which belonged only to YHWH in the Old Testament, or that spoke explicitly of YHWH and was now applied to Jesus himself. But the question is, how do we balance the humanity and deity of Jesus in one person? And this was the challenge of the early Christian discussion concerning the first four centuries of Christendom, and finally was established as the doctrine of the Two Natures of Christ. Conclusion: The Two Natures of Christ. Holding in perfect balance both the humanity and the deity of Jesus has been one of the great challenges of Christianity, and still to a large degree remains a mystery to us. However, Christian theologians have grappled with this question. For the early apostolic preaching, Jesus’ humanity and divinity was assumed. But since heretical sects came to emphasize either one or the other, the church had to give a definitive answer as to this seeming conundrum. Michael Bird summarises the doctrine when he writes, “the view that won the day was that Jesus had two natures – divine and human – which were united but unmixed in his one person. This view is called hypostatic union and was formally ratified by the church at the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451). The basic thrust of the Council was to affirm that Christ possesses everything true of a person and he possesses everything true of both the human and the divine natures.”[14] In other words, the eternal person of the Son, whom John calls “The Word” (John 1:1), and who Jesus said existed with the Father “before the world existed” (John 17:5), this person possesses a divine nature that is eternal, and it was this person that “became flesh and dwelt among us,” and in his taking on flesh he also took on a second nature, namely a human nature, and therefore the person of the Son, the eternal Word, now had two natures, both divine and human, without the one diminishing the other. Both natures, therefore, exist in the one Person. This is Jesus Christ, the Son of God, our Lord. [1] N. T. Wright, 1996. Jesus and the Victory of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pg. 5. [2] Ibid, pg. 11. [3] Sawyer, J. F. A. 1993. Messiah (in Metzger, B. M. & Coogan, M. D. eds. The Oxford Companion of the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press), pg. 513ff. [4] Ibid. [5] See http://ntwrightpage.com/2016/04/05/jesus/ [6] Ibid. [7] See Calvin, J: II:XV:I-VI. [8] Calvin, J. 1559. II:XV:II (transl. Battles, F. L. & McNeill, J.T. ed. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion Vol. 1. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press). [9] Müller, M. 1993. Son of God (in Metzger, B. M. & Coogan, M. D. eds. The Oxford Companion of the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press), pg. 710. [10] Ibid. [11] Ontological: in other words, as he is in himself at the core of his being. [12] See Pannenberg, W. The Apostle’s Creed In Light of Today’s Questions. London: SCM Press Ltd, pg. 68, “That as the Son of God Jesus belongs to the essence of God himself is also brought out through the term ‘Lord.’” [13] Hagner, D. A. 2012. The New Testament: A Historical and Theological Introduction. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, pg. 172f. [14] Bird, M. F. 2016. What Christians Ought To Believe. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, pg. 82. Morne MaraisI am the pastor/elder of a small suburban church on the outskirts of Cape Town. I enjoy coffee, theology, and fresh air. We are grateful to have all three in abundance.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2018

Author Morne Marais

|